In our previous blog we discussed the importance of identifying whales from each other and more specifically how you can do so with humpback whales. In this blog, we will be focusing on another type of whale, orcas! Also known for their notorious name, killer whales.

Orcas can be found in all oceans, but they are most often found in cooler waters such as the Southern Ocean, the North Pacific, and North Atlantic. They are possibly the most recognizable species overall other than dolphins, but what you might not know is the fact that orcas are actually subdivided into distinct ecotypes.

Yes! You read that correctly, not all orcas that are seen are the SAME type of orca. What exactly does “ecotype” mean? An orca’s ecotype is defined by their main qualities behaviorally and physically.

Ecotypes can be defined as a population (or subspecies) that has adapted to its local environmental conditions. Those individuals who adapted the most to the prevailing conditions produce the most offspring which results in more successful individuals carrying genes that are partly responsible for their success in that environment. Thus, the adaptations of these ecotypes are based on the interactions of their own special sets of genes with their own environment.

Ecotypes can be broken down by the differences in appearance, diet, genetics, acoustic dialects and social organization.

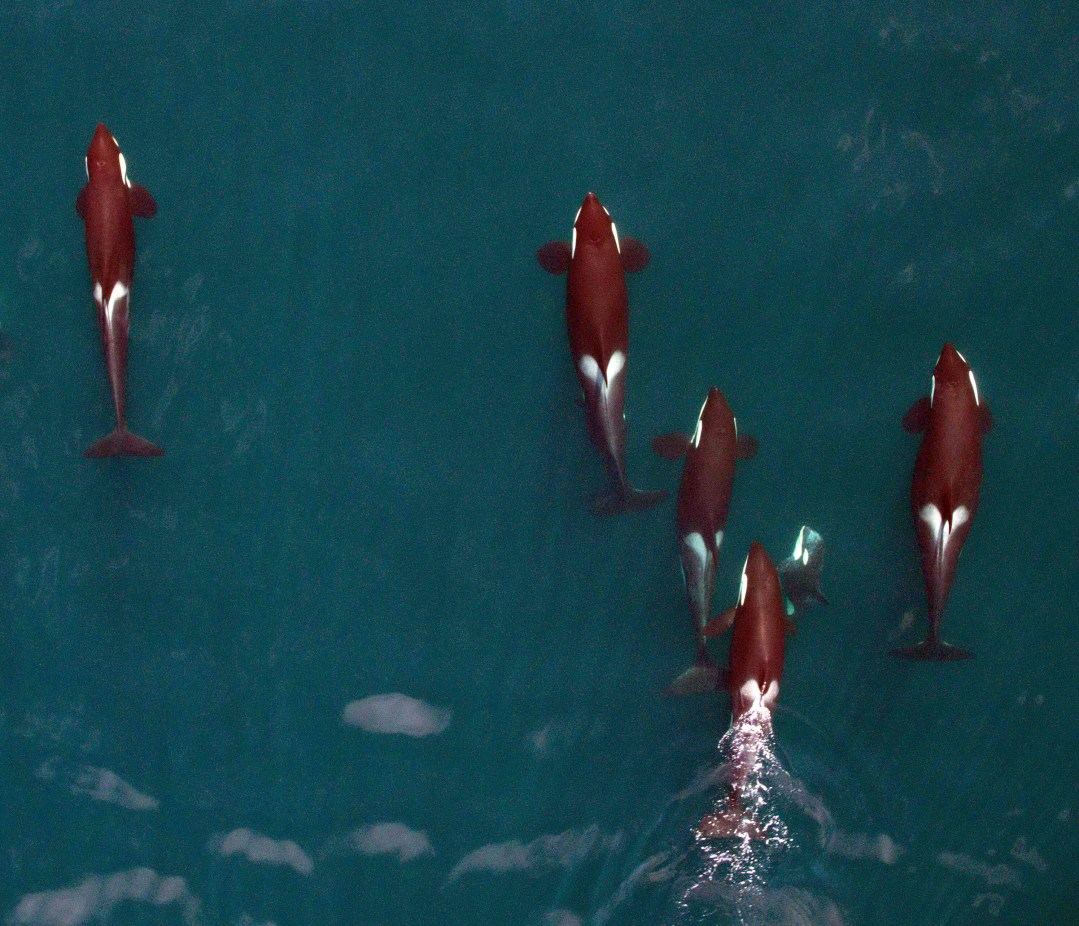

Right now in the Eastern North Pacific Ocean (off the West Coast of the U.S. and Canada), the three primary ecotypes are known as Resident, Bigg’s (Transient), and Offshore. The complex societies they live in can be made up of family and/or fluid groups. As of now it has been observed that Residents tend to be mainly in family groups while Transients are sometimes fluid or family oriented and Offshores do not have enough observation to officially conclude. What these three ecotypes have in common is the fact that they are all black and white (obviously) and the males are larger than the females.

Let’s break down some of the basics for these three ecotypes!

Resident Orcas

- Range: California to Aleutian Islands; distinct populations have smaller home ranges

- Communities: Three currently recognized distinct Resident populations in the Eastern North Pacific, named by general location relative to other groups: Southern, Northern, & Alaskan. Alaska’s population is further divided into three sub-populations.

- Social Organization: Highly social and live in large family groups where male and female offspring stay with their mothers for life. Populations can be identified acoustically by shared call types, and each pod has a distinct dialect or “accent”.

- Diet: Chinook Salmon

- Fin Fact: Resident Orcas are matriarchal – elder females are the leaders of their groups.

Transient / Bigg’s Orcas

- Range: Coastal and offshore waters of Southern California to Arctic Circle; subpopulations have smaller home ranges.

- Social Organization: Some offspring stay with their mothers, others will continue to closely associate with their family group. They tend to live in smaller related pods, more fluid composition.

- Diet: Marine mammals (including seals, sea lions, dolphins, porpoises, whales) and squid.

- Fin Fact: Diverged from other North Pacific orca lineages as much as 700,000 years ago.

Offshore Orcas

- Range: Occupy the largest range, from Southern California to the Aleutian Islands; live far offshore, usually over the continental shelf edge.

- Social Organization: Highly social, live in large groups (typically seen in groups of 50-100 individuals).

- Diet: Fish and sharks, full diet is still unknown.

- Fin Fact: Teeth are often worn out, likely from the rough skin of sharks.

Unlike humpbacks, orcas do not carry many colorful distinctions and because of this there is a bit more of a challenge when identifying them individually. Therefore, identifying them requires a different approach. A simple observation to make when trying to determine which orca you are seeing is to start off with their sex. Observing a smaller dorsal fin can help you recognize it as a female. Adult male orcas are known to have significantly larger dorsal fins – up to 6 feet high! This is the simplest and most obvious distinction, although there are some exceptions. Juvenile males sometimes have small fins and they fully sprout their fins at about 15 years old. This can make it challenging to distinguish a male from a female, but seeing a calf with an orca always determines it to be female.

To become an expert, once you know which ecotype you are seeing, you are going to want to look at five main qualities when observing individual orcas.

Saddle Patch & Dorsal Fin

The saddle patch is located on the upper side of the orca’s back, behind their dorsal fin. It is a very light-colored pigmentation that is unique to each individual. It typically can be observed easily when the whale breaks the surface of the water and as seen below, can carry many variations. The best time to notice the subtle differences are when they are calves because the saddle patches are faint. Dorsal fins are also ways to distinguish and ID individuals due to imperfections like scarring that can form. This technique is great for Transient orcas since they tend to have saddle patches that are almost identical.

Matriline

The easiest ones to spot from a pod are usually the males. Once located, observations can be made about the family dynamic. How many calves, females, juveniles and males are there in total? Mothers can be easily distinguished from males when they are with their calf.

Eye Patch

A common misconception is that an orca’s eyes are located in the white marking on each side of their face. Actually, this mark is located right behind their eyes. Each orca’s white eye patch is unique as well and if closely observed, can be a great tool for distinguishing them.

Fluke

Just like with humpback whales, a fluke can sometimes be used to identify an orca based on its trailing edge, shape and any cuts/nicks. This is not usually the method of choice because all orcas have an all black dorsal fluke and white ventral fluke. In addition, it is very uncommon for them to flaunt their flukes at us unless they are engaged in unique behaviors. It is not nearly as common seeing their tails the way it is with humpback whales, but it can be helpful on the occasions when we do see it.

Echolocation

One of the amazing qualities orcas have is the fact that they are very vocal amongst each other. So much so, that each pod, population, or ecotype can be identified by their vocal patterns and the vocalizations they emit. Each click, whistle or pulsed call can be distinct and are primarily used amongst those in the same pod, not outsiders. Transients are not actually known for making any vocalizations, so that is one less ecotype to worry about! If you listen below, you can get an idea of what their sounds are like.

If you’re lucky enough to see orcas while at sea, use the tips shared above to see if you can distinguish what ecotype and pod you have come across! And if you’re on a Whale SENSE whale watch, ask the onboard naturalist about identification catalogs that may be available in that area!

To learn more about Orcas, visit:

To read our previous blog on how to identify Humpback whales, visit:

Stay tuned for our next blog which will review how North Atlantic right whales are identified!